Benchmarking Symmetric Crypto on the Apple A7

In this blog post I will present results from benchmarking the symmetric crypto primitives BLAKE2 and NORX on the Apple A7. One might ask, why target the A7 in particular, what’s so special about it? I will cover that in a moment, let me first give a brief overview on the two crypto algorithms.

- BLAKE2 is a high-speed and high-security hash function and successor to BLAKE, one of the finalists of NIST’s SHA3 competition. It was designed by Jean-Philippe Aumasson, Samuel Neves, Zooko Wilcox-O’Hearn and Christian Winnerlein. The intention behind BLAKE2 was to design a secure hash function which is not only faster than the winner of the SHA3 competition Keccak (in fact BLAKE is generally faster than Keccak in software), but in particular faster than MD5. The latter is a hash function shown to be insecure on multiple occasions, but unfortunately is still quite wide-spread. It seems the designers hit a nerve with BLAKE2, since the number of projects adopting it increases steadily. For more information on the hash function refer to the BLAKE2 research paper. As an alternative, one can find a summary with additional background information on the Least Authority blog.

- NORX is a brand-new authenticated encryption scheme, which was designed by Jean-Philippe Aumasson, Samuel Neves and myself. It uses well analysed building blocks from BLAKE2 and Keccak, but also introduces new design elements, which allow parallel encryption for high data throughput, increase hardware friendliness and robustness against side-channel attacks. NORX has been submitted to the CAESAR competition, which searches for proposals that might one day replace AES-GCM. The latter has some unwelcomed weaknesses, but is currently the de-facto standard for authenticated encryption. For more information on NORX, you can either refer to the offical specification or to the tl;dr version on cybermashup which gives a good overview.

Why benchmarking on the Apple A7?

At the time when we prepared the NORX document for submission to CAESAR, we made several benchmarks on various platforms, ARM and Intel alike. Two weeks after the CAESAR deadline an article on Anandtech appeared that showed the latest revelations about Apple’s A7 architecture, which sounded very promising and awakened our interest. As chance would have it, I had one of the new iPad Airs lying around, which is equipped with an A7. Unfortunately, it was already too late to include any more benchmarks in the NORX submission document. Another problem was that I didn’t have an Apple developer license, which is required to run your own apps on iOS. Thus I’ve postponed the task to a later time. Now, over a month after the CAESAR deadline and equipped with a new, shiny developer license from the Apple iOS Developer University Program, I came back to the undertaking. Before I go into the details of the benchmarking process and describe the results, lets have a more detailed look at the A7 chip.

So what’s the deal with the Apple A7?

In September 2013, Apple introduced the A7, a 64-bit ARM processor, during the presentation of the iPhone 5s. Two months later, a slightly enhanced version of the new processor was also included in the iPad Air and the iPad Mini 2. Although the A7 was not the first 64-bit ARM processor to date, it was the first for usage in consumer smartphones and tablets. During their keynote, Apple claimed that the A7 has a desktop-class architecture and up to twice the CPU and graphics power compared to its predecessor, the Apple A6.

A stop at Wikipedia reveals first insights on the architecture of the A7:

The A7 features an Apple-designed 64-bit 1.3–1.4 GHz ARMv8-A dual-core CPU, called Cyclone. The ARMv8-A instruction set doubles the number of registers of the A7 compared to the ARMv7 used in A6. It now has 31 general purpose registers that are each 64-bits wide and 32 floating-point/NEON registers that are each 128-bits wide. … The A7 has a per-core L1 cache of 64 KB for data and 64 KB for instructions, a L2 cache of 1 MB shared by both CPU cores, and a 4 MB L3 cache that services the entire SoC.

tl;dr: the A7 has more and bigger registers and caches than its predecessor the A6, which should improve general performance.

The author of the already mentioned Anandtech post managed to reveal even more of Cyclone’s secrets in a series of articles. Through intense testing and tedious reverse engineering of commits, pushed to the public branch of the LLVM project by the Apple developers, he found out several interesting details about the architecture. Among other things, his analysis shows that the A7 has 4 Integer ALUs, is capable of 4 Integer and 2 floating point additions per cycle, i.e. up to 6 operations per cycle and has a reorder buffer size of 192 micro-ops. These are quite impressive numbers for an ARM processor, especially in comparison to normal desktop CPUs. According to this article, the latest Haswell microarchitecture can do up to 8 operations per cycle and has a reorder buffer size of 192 micro-ops. Former architectures, like Sandy/Ivy Bridge, are capable of up to 6 operations per cycle and have a buffer size of 168 micro-ops. At least from that perspective, Apple’s Cyclone is positioned in between the two Intel microarchitectures. The number of Integer additions a processor is capable to execute per cycle influences heavily the performance of crypto algorithms running on that CPU. The higher the number, the better the expected performance of the crypto primitive (at least for non-NEON-optimised variants). Okay, I could go on with the analysis of the pros and cons of the A7, but let’s leave it at that and get back to the topic of this post instead.

How did the setup look like?

I benchmarked standard and NEON-optimised versions of the above crypto algorithms and used the following setup for my experiments:

- BLAKE2b and BLAKE2s: For the standard variants I used the implementations found in SUPERCOP. The NEON-optimised versions are not publicly available, yet, but Samuel thankfully provided me with copies of the code. The benchmarking framework for BLAKE2 was taken from its official GitHub repository.

- NORX3241 and NORX6441: Implementations of the algorithms and the benchmarking framework are all available through GitHub.

All implementations are compiling and running out-of-the-box on iOS. However, some modifications to the benchmarking framework were necessary, to allow computation of CPU cycles on iOS. After some searching, I found an article in the Mac developer documentation. I used the second of the described variants, which also works on iOS. For the concrete implementation, I refer to the bench.c file found here. Since the code is compiled for iOS, there’s not much choice left for the compiler:

clang --version

Apple LLVM version 5.1 (clang-503.0.40) (based on LLVM 3.4svn)

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin13.1.0

Thread model: posix

For the flags I just -O3 for standard implementations and -O3 -march=arm64 -mfpu=neon for NEON-optimised variants.

What are the results?

Here you go:

Apple A7

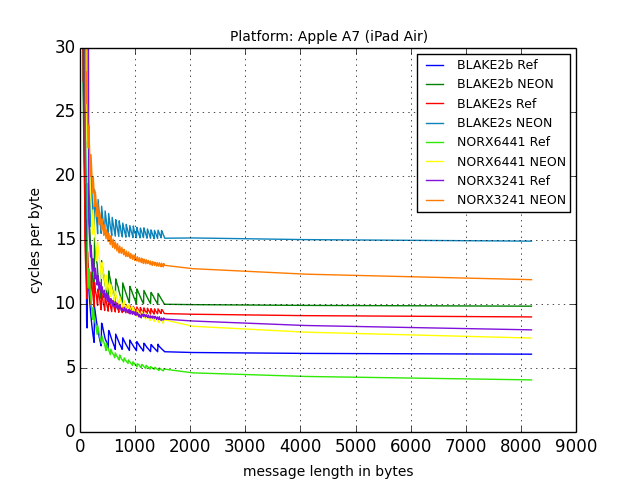

The picture above shows the speed of the various primitives in cycles per byte (cpb) as a function of the message length (in bytes). I’ve generated it using this script and the excellent matplotlib. The raw data (in csv format) can be downloaded here. The following list is an excerpt of the data and shows the cpb of the algorithms on long messages:

- BLAKE2b: 6.08 (Ref) and 9.83 (Neon)

- BLAKE2s: 8.99 (Ref) and 14.91 (Neon)

- NORX6441: 4.07 (Ref) and 7.34 (Neon)

- NORX3241: 7.98 (Ref) and 11.90 (Neon)

As a general rule of thumb: The lower the cpb numbers the better the performance. Looking at the table, the first thing that becomes apparent are the truly impressive top speeds of 6.08 cpb for BLAKE2b and 4.07 cpb for NORX6441. These values translate to throughputs of about 230 MiBps for BLAKE2b and to about 343 MiBps for NORX6441 (assuming a frequency of 1.4 GHz as available in the iPad Air). For comparison, AVX2 implementations of BLAKE2b and NORX6441 achieve on Haswell about 3.15 cpb and 2.51 cpb, respectively. Throughputs are bigger though, due to higher frequencies of the Intel architecture. On the other hand, the numbers for the A7 are only for standard (and non-optimised) versions, which leads me directly to the second observation. Normally, one would expect that NEON-optimised implementations have a performance advantage, as it was shown in this paper. However, that’s somehow not the case for the A7, where the NEON versions are slower than their normal counterparts by a factor of up to 1.8 (in case of NORX6441). This is quite surprising and the only somewhat reasonable explanation that I can currently present is that the algorithms seem to benefit a lot more from the Integer ALUs and “free-shift operations” than from the NEON vector instructions. It would be interesting to investigate the concrete reasons and find out if these speculations are true. Maybe it’s just a phenomenon of BLAKE2 and NORX, which have a very similar layout. In any case, I’d be happy to hear from anyone who might have an explanation for this rather strange behaviour.

Conclusion

From the viewpoint of cryptography, Apple’s claim that the A7 is desktop-class seems to be no exaggeration. High-security cryptography at surprisingly high speeds is easily achievable on that platform, and in particular even without NEON instructions, which is all the more surprising. It would be interesting to see some benchmarking results on an iPhone 5s and/or iPad Mini 2. I hope this blog post motivates people to measure other symmetric primitives on Apple’s Cyclone architecture, to get a broader overview on its cryptographic capabilities. Maybe this would also help to figure out the reasons behind the bad behaviour of NEON-optimised crypto algorithms on the A7.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Samuel Neves and Jean-Philippe Aumasson for helpful discussions and valuable comments on drafts of this article.