ByzCoin: Securely Scaling Blockchains

This post originally appeared on Emin Gün Sirer’s blog Hacking, Distributed.

It is no secret that Bitcoin is currently in the midst of a severe scalability crisis. Its steadily-rising popularity has been accompanied by an ever increasing volume of transactions (tx), bringing the cryptocurrency to its knees. Sometimes the whole system is overloaded to a point of unusability. As an example of how bad the situation has become, on March 3, 2016, Bitcoin hit its 1MB-per-block transaction processing limit, resulting in a backlog where up to 30’000 transactions sat in the queue waiting to be processed for hours and in some cases for days.

Below, we first summarize Bitcoin’s scalability crisis in more detail and identify one of the core problems that led to the current situation. Then we present an overview on ByzCoin, an enhancement of Bitcoin proposed by EPFL’s Decentralized and Distributed Systems (DEDIS) lab; ByzCoin provides a solution to resolve the scalability issues of Bitcoin and demonstrates how to securely process hundreds of transactions per second among hundreds to thousands of decentralized miners. We conclude by discussing the challenges of deploying ByzCoin on top of Bitcoin, and we outline some initial ideas how a concrete deployment might be approached.

Bitcoin’s Scalability Crisis

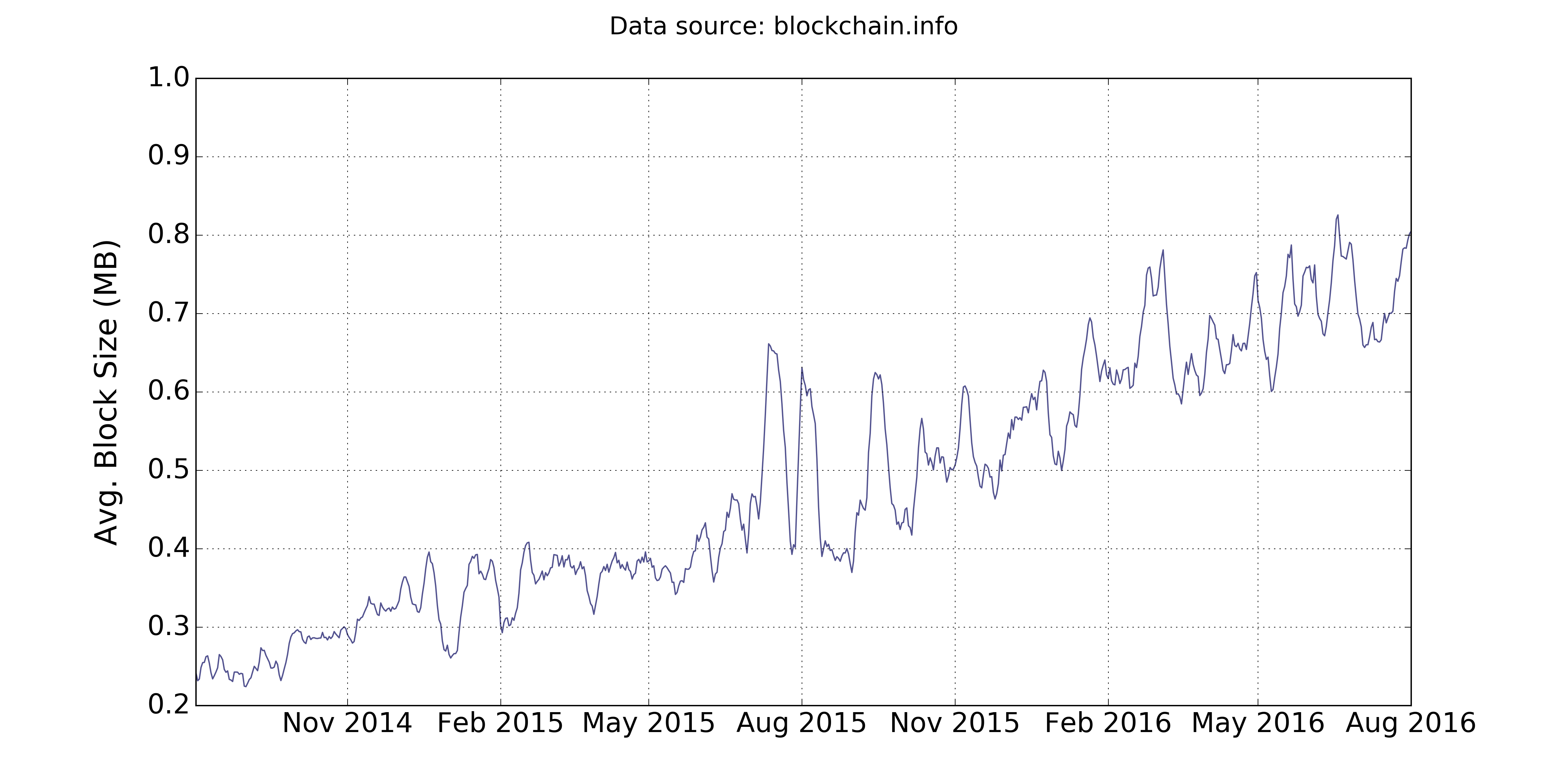

Bitcoin is a self-regulating system that is powered by a decentralized network of computers. The miners, special nodes in the network, form the engine of the cryptocurrency. In addition to storing a complete copy of the distributed ledger, the blockchain, each miner bundles transactions into blocks of up to 1MB and then tries to solve a cryptographic puzzle. Once a miner finds a solution, the so-called proof-of-work, he is entitled to add the block to his copy of the blockchain. Afterwards, the miner broadcasts the block together with the proof-of-work so that other nodes can verify the solution and—if valid—extend their blockchain-copy as well. Due to the design parameters of Bitcoin, the discovery of such a cryptographic proof-of-work solution occurs approximately every 10 minutes. The highest transaction throughput is therefore effectively capped at the maximum block size divided by the block interval. To be able to handle the steady-rising load of transactions and keep the system operational, miners have been forced to continuously increase the block size. The repercussions of this behavior can be seen in the following graph that shows Bitcoin’s average block-size increase over the last two years.

Average Bitcoin blocksize

Soon the average block size will hit the maximum limit of 1MB, at which point all sorts of bad things will start to happen. For example, transaction backlogs, like the one mentioned in the introduction, will become much more frequent, if not permanent. Looking at throughput, Bitcoin currently processes about 2.5 tx/sec on average and is capable of handling at most 7.0 tx/sec. In contrast, VISA handles 2000 tx/sec on average and up to 56’000 tx/sec during peaks. A back-of-the-envelope calculation indicates that, to process the 30’000 transactions mentioned above, Bitcoin would need over 70 minutes running at maximum throughput, whereas VISA is capable of handling the load in below one second. Recent studies suggest that the current Bitcoin design is capable of processing at most 27 tx/sec by increasing the block size to 4MB, while still retaining its security guarantees. Nevertheless, the throughput would still be two orders of magnitude below VISA’s capabilities. And throughput is not the only problem: A huge transaction-confirmation latency prevents Bitcoin from handling transactions in real-time. Satoshi Nakamoto, the mystery-shrouded pseudonymous inventor of Bitcoin, recommended considering a transaction to be “confirmed” only after another six blocks are added on top of a block. Obviously, there is a large performance gap between Bitcoin and mainstream payment processors. To reduce this gap, the key questions are the following:

Is it possible to scale decentralized, permissionless cryptocurrencies in a secure way to match the performance of mainstream payment providers in terms of transaction throughput, as well as confirmation latency?

What does it take to get there?

These questions sparked fierce discussions within the Bitcoin community but, so far, have not lead to a clear path forward. Instead, a fragmentation of the community occurred, leading to multiple Bitcoin spin-offs (Core, XT, Classic). Most of the proposed solutions are more or less band-aids that might mitigate the most pressing concerns to a certain extent but do not address the actual problem. There are also exceptions, such as Bitcoin-NG, which indicate that Bitcoin has to undergo a much more fundamental re-design to achieve a sustainable solution to many of the cryptocurrency’s current problems.

Strong Non-probabilistic Consistency

One core problem in Bitcoin’s current design is its consensus kinds of attacks and prevents the realization of secure real-time transactions, where goods, services, and currency can be exchanged instantly as in classic payment systems.

To use Bitcoin for real-time trades, we need to eliminate its lazy fork-resolution mechanism and adopt strong consistency, a more proactive approach that guarantees transaction persistence. Strong consistency offers the following three important advantages to cryptocurrencies:

All miners agree on the validity of the blocks right away, without wasting computational power to resolve forks.

Clients need not wait extended periods to be certain that a submitted transaction is committed; as soon as it appears in the blockchain, the transaction can be considered confirmed.

Once a block has been appended to the blockchain, it stays there, forever (as long as there is an honest majority of miners). This property is also often referred to as forward security.

Now let’s explore an approach how to obtain strong consistency in Bitcoin and thereby get all of the desirable properties above.

Byzantine Fault Tolerant Consensus for Bitcoin-like Cryptocurrencies

ByzCoin, to be presented later this month at USENIX Security ‘16, is a novel scalable Byzantine fault-tolerant (BFT) consensus protocol that provides strong consistency, while scaling to processing throughputs of hundreds of transactions per second, among hundreds to thousands of decentralized miners. ByzCoin utilizes an adaptation of PBFT and introduces four key improvements over Bitcoin:

ByzCoin’s improved PBFT-like consensus mechanism commits Bitcoin transactions irreversibly within seconds.

ByzCoin preserves Bitcoin’s open-membership property by dynamically forming hash power-proportionate consensus groups that represent recently-successful block miners.

ByzCoin uses communication trees to further optimize transaction commitments and verification under normal operation while guaranteeing safety and liveness under Byzantine faults.

ByzCoin decouples the election of a new leader from transaction verification, an approach inspired by Bitcoin-NG, that enables ByzCoin’s transaction throughput to further increase.

Together, all these optimizations enable ByzCoin to achieve throughputs higher than PayPal currently handles, and to provide low confirmation latencies. Another benefit of ByzCoin’s fast transaction commitment, ranging from a few seconds up to at most one or two minutes after submission, is the mitigation of double-spending and selfish mining attacks.

ByzCoin’s Design

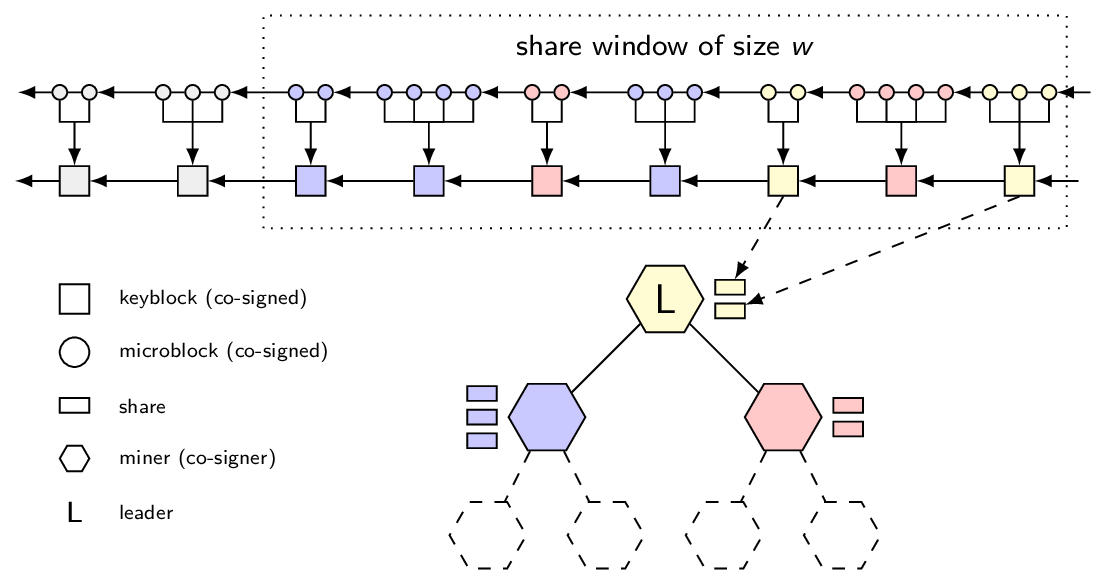

The following graphic illustrates ByzCoin’s design:

ByzCoin design overview

The lower part of the above picture shows ByzCoin’s consensus group that is comprised of recently-successful block miners and uses a PBFT-like mechanism to reach consensus. Instead of PBFT’s MAC-based authentication, which has quadratic communication and computation complexity, ByzCoin uses CoSi, a distributed protocol that makes large-scale, decentralized, collective signing practical. On a high level, CoSi works roughly as follows:

The oversimplified summary is that the [CoSi] protocol involves compressing hundreds or thousands of signatures into a single one that can be verified almost as simply and efficiently as a normal individual signature. — Bryan Ford

Overall, tree-based collective signing reduces communication complexity from quadratic to logarithmic, enables third-party verifiability, and enables us to verify signatures in constant-time complexity. We will spare you the details on how exactly CoSi is used to reach a decision in ByzCoin’s consensus group and instead refer you to the research paper for more information. Another feature that ByzCoin adopts from PBFT is the role of the consensus group leader whose task is to bundle transactions into blocks and initiate new signing rounds. All actions, however, taken by the leader have to be approved by a two-thirds supermajority of the consensus group members, which effectively leads to strong consistency and all of its benefits discussed earlier. In case the leader misbehaves, the miners in ByzCoin’s consensus group can start a voting round and dismiss the Byzantine node but only if, again, a two-thirds supermajority approves. The requirement of the two-thirds supermajority for decision making comes from Byzantine agreement theory that permits at most f malicious/faulty nodes among a total of 3f+1 nodes. Another important part that we have not discussed yet is the mechanism for electing the leader of the consensus group, which brings us to the next component of ByzCoin’s design.

The upper part of the above picture shows ByzCoin’s blockchain which is divided into two interdependent sub-chains: one for keyblocks and one for microblocks.

Keyblocks are used to manage ByzCoin’s consensus group membership. These blocks are generated by the miners through proof-of-work roughly every 10 minutes, as in Bitcoin, and are collectively signed by ByzCoin’s consensus group. Keyblocks form a regular blockchain. A miner who successfully mines a new keyblock is rewarded with a consensus group share, a proof-of-membership, thereby gains entry into the consensus group, if he is not already a member, and becomes the next group leader. A fixed-size sliding window mechanism constitutes the total number of available shares: Any share beyond the current window expires and miners who no longer hold any valid shares drop out of the consensus group. The number of valid shares in the possession of a miner reflects his voting power within the consensus group, when committing transactions. Moreover, this number determines the portion of coins a miner receives as a reward, when a new keyblock is found. In other words, ByzCoin rewards not only the node that mines a new keyblock but instead splits, proportionate to the valid shares each miner holds, the produced coins among all miners of the consensus group. ByzCoin also uses this technique to split transaction costs as a reward, once no more coins can be mined. The proof-of-membership approach ensures liveness, as dormant miners are removed from the consensus group and the share-proportionate rewards further incite all miners to remain active and contribute to the progress of the system.

Microblocks, on the contrary, contain transactions, are proposed by the current leader, and, as they do not require proof-of-work, are committed much more frequently by the consensus group. Each microblock contains, in addition to the list of transactions, a hash of the last microblock to ensure total ordering, as well as a hash of the leader’s keyblock to identify the era the microblock belongs to. Even though microblocks are created by the consensus group leader, ByzCoin’s witness-mechanism deters leaders from misbehaving (such as mounting double-spend attacks), because any misconduct would be immediately detected by the other group members, which in turn can trigger a view change thereby removing the malicious node.

Performance Evaluation

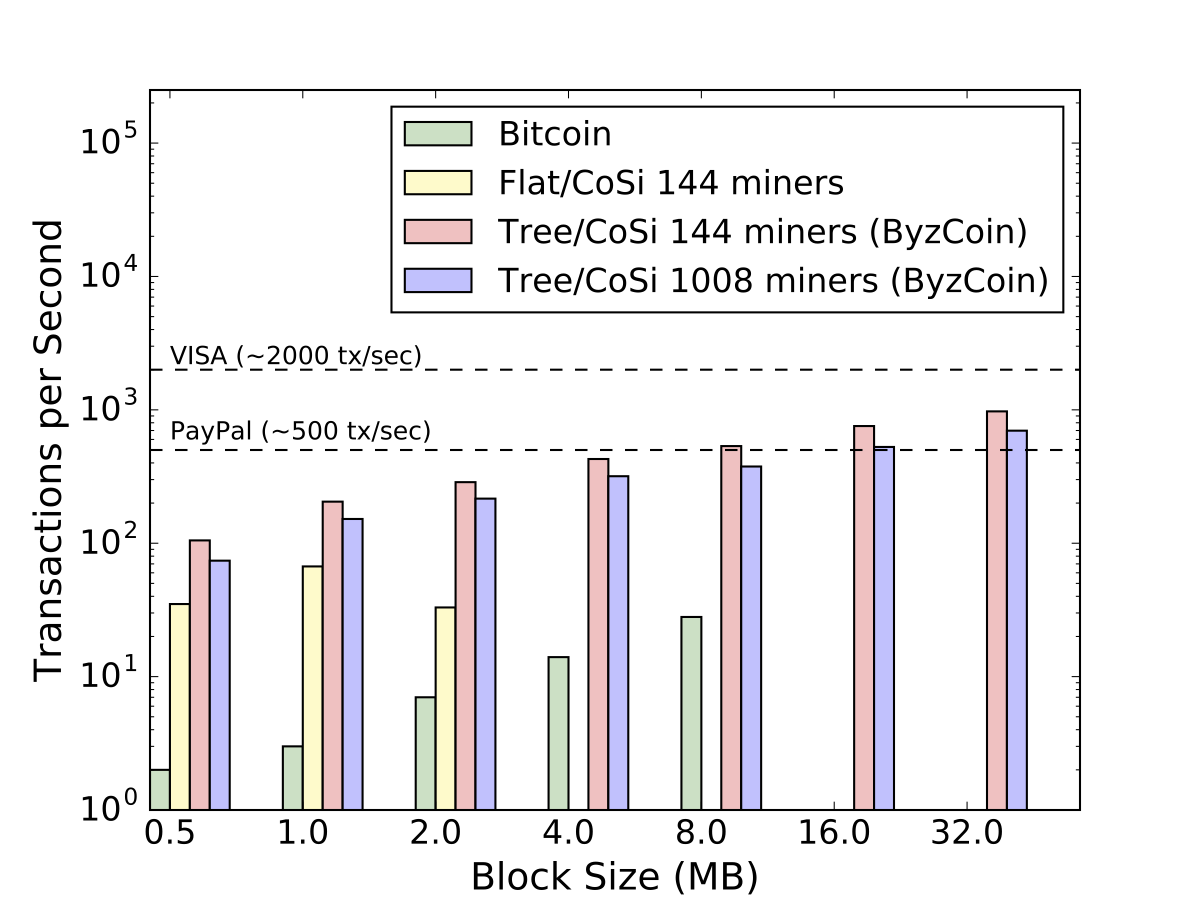

To evaluate the design of ByzCoin, we wrote a prototype, available on GitHub as a part of the DEDIS cothority project, and conducted thorough experiments, measuring transaction confirmation-latency and throughput. We experimented with consensus group sizes between 144 and 1008 nodes, which corresponds to a window of successful keyblock miners ranging from the last day’s up to the last week’s. The graph below shows ByzCoin’s throughput in comparison to other systems. The data for our simulations is based on actual transactions from a portion of the Bitcoin blockchain.

ByzCoin throughput

The average latency we measured, for example for 32MB blocks (~66000 tx) and a consensus group size of 144 members, was around 90 seconds. For this particular configuration, ByzCoin’s throughput (~700 tx/sec) outperforms PayPal’s as you can see in the graph. A more elaborate discussion of ByzCoin’s performance evaluation can be found in the research paper.

Deployment Challenges

Developing a reasonable deployment strategy for ByzCoin involves solving at least the following three challenges:

Roll out code that is backward-compatible with the current Bitcoin system until a critical mass of miners supports the new ByzCoin consensus.

Build the initial consensus group which then switches to the new consensus mechanism once the above critical mass appears.

Handle (hopefully rare) PBFT deadlock events, e.g., because too many miners disappear in too short a time and no two-thirds supermajority is or will ever again be available in the current consensus group.

To address the first two challenges, we can utilize the already running Nakamoto consensus as a bootstrapping mechanism. From an outside point of view, Bitcoin would basically operate as usual, so long as the bootstrapping is not finished. A few things change from the perspective of the miners though: each miner puts his public key and contact information (IP address/port number), respectively, into every block he creates. Including the public key enables a miner to claim the block as a share once he finds the necessary proof-of-work; the contact information is required so that consensus group members are able to find each other and create the communication tree. As soon as the number of distributed shares hits the maximum share-window size, all miners in the consensus group switch to ByzCoin, the last miner to join the group becomes the leader, and the group co-signs the leader’s keyblock. Afterwards, the leader creates the new microblock-subchain from his keyblock and starts creating and submitting microblocks to the co-signing consensus procedure. To handle the third challenge, we can use the Nakamoto consensus as a fall-back option: If miners notice a lack of progress from the PBFT consensus group for too long (perhaps after several view-changes), they return to committing transactions as part of their keyblocks, just as in vanilla Bitcoin, thus effectively reverting the system to its pre-ByzCoin agreement mechanism. As soon as a certain threshold of shares is again distributed, miners can re-start ByzCoin’s consensus. Another option would be to use Bitcoin-NG as a fall-back mechanism, which has the advantage of providing similarly good performance as ByzCoin but guarantees not all of ByzCoin’s security features.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we have presented a brief overview on the novel ByzCoin consensus mechanism. We have illustrated how the adoption of a consensus mechanism, with strong non-probabilistic consistency enables open-membership cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, to achieve high transaction-throughput and to keep confirmation latencies low. ByzCoin offers not only a performance benefit but also mitigates double-spending and selfish mining attacks. Bitcoin is one option where the ByzCoin consensus might be used but also other cryptocurrencies such as Ethereum, Zcash, and even permissioned blockchain-systems such as Hyperledger might be interesting deployment targets. Beyond that, it would be interesting to explore to what extent non-blockchain-based payment systems, such as Interledger, are able to benefit from a ByzCoin-like consensus mechanism. If you have any thoughts (improvements, criticism, etc.) about this blog post, we would be very happy to receive your feedback. You can get in touch with us through the DEDIS cothority mailing list.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Emin Gün Sirer for giving me the chance to present our work on his blog. Moreover, I wish to thank my colleagues Bryan Ford, Nicolas Gailly, Linus Gasser, Ismail Khoffi, Eleftherios Kokoris-Kogias, and Kirill Nikitin who all provided invaluable feedback on early drafts of this post.